Did you know Latvia is one of the world's top performers when it comes to nominal indicators like number of students per capita? The same probably applies with regard to the number of higher education establishments (34!) per capita. Since more than half of all the graduates are in the social sciences, of which I would say many are in business administration and economics, I wouldn't be surprised if we had the largest number of economists per capita. Yet anyone who lived here long enough knows that how things look 'on paper' is not the same as they really are. Far from it, sometimes.

One can start asking all these uncomfortable questions. Why is one of the world’s most educated countries so poor? Having produced so many economists, how did it end up having what may soon surpass the Great Depression? And hey, with what happened over the last year, and in the run-up to this, where have all the economists from these numerous universities were? What have we heard from them? Then there are these smaller but fascinating questions. Like why is “Latvijas Ekonomists” (Latvian Economist) journal not named “Latvijas Grāmatvedis” (Latvian Accountant), which is what it really is?

Am I the only one feeling that something is deeply wrong with higher education generally (and economics education specifically) in this country? Of course, a feeling is not enough. One needs the evidence. Here is a link to a discussion paper I have produced for the Strategic Analysis Commission a few months ago. An English version has been published as a policy paper (i.e. non peer-reviewed) in the Baltic Journal of Economics.

In a nutshell, the argument goes like this. Evaluating professors and scientists is tough. They’ve spent many years investing in some very specific human capital. If you didn’t make the same investment, it’s hard to understand the ‘value’ of what they do. Yet evaluate you must. For instance, scientists always ask for taxpayers’ money. How are the taxpayers to know they’re getting a good return on their investment? A solution is quite simple. Find someone who has made the same human capital investment and ask them whether what the first guy does is any good. Ideally, that ‘someone’ should not be a good friend of the guy you’re trying to evaluate. That’s what the “peer-review system” is all about. Quality of scholars is assessed by the number of publications they have in international peer-reviewed journals, where a publication is only possible if at least two anonymous referees (scholars working in the same field) say that what you did is good enough. Note that INTERNATIONAL is fairly important since it means a large market of potential referees and smaller likelihood that a referee would be a friend of whoever is being evaluated. Is it a perfect indicator? Probably not. But it’s the best we’ve got. So how are Latvian scholars doing with regard to producing English language articles in international peer-reviewed journals?

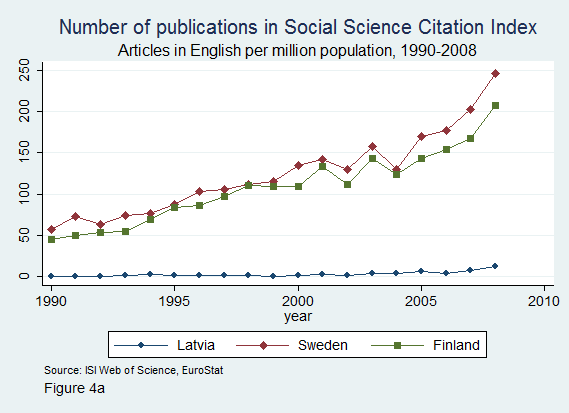

First, a comparison of Latvia to Sweden and Finland with regard to the so-called SSCI publications (a widely used standard). Note, English is NOT an official language in either Finland or Sweden.

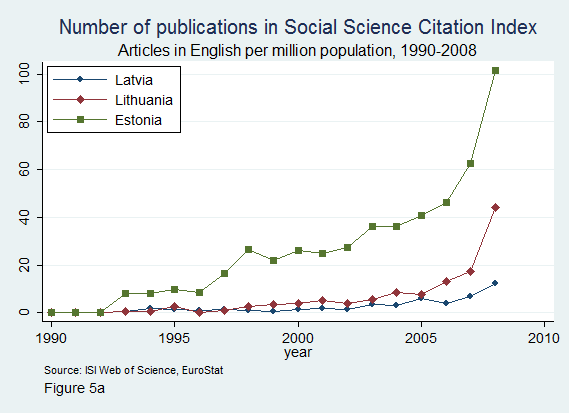

Now, a comparison of Latvia with Estonia and Lithuania.

Ouch… right? The question is, if most Latvian scholars (in social sciences) can’t produce peer-reviewed publications in international journals, can they be good professors? The answer depends on whether you buy into the argument there is correlation between research and teaching (and there are some very notable exceptions!). But here is some more evidence.

Each year we run the so-called Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), a survey of 2,000 adults. Sometimes we insert additional questions. So, in 2007 (i.e. before the crisis!) we also asked whether “the state should fix prices for basic goods”. Somewhat strikingly, 92 percent of all respondents agreed with the statement (yes, this is still a “Latvian Socialist Republic”). But maybe higher education (received after independence) makes a difference? After all, a standard Econ 101 course is supposed to teach you that it’s not a very good idea for the state to fix prices. Now, take a wild guess how many young (<37 years old) adults with higher education agree with the above statement? Nearly 90 percent… One more “Ouch”, right?