On November 27, the Latvian Parliament (Saeima) decided to establish a parliamentary investigative commission with the aim of identifying problems in immigration regulation at the national and EU levels, as well as in the work of executive institutions. The decision undertakes an in-depth evaluation around migration, that could provide the necessary impetus for the adoption of several long-delayed decisions.

Centre for Public Policy PROVIDUS advocates for knowledge- and data-driven policymaking by conducting policy analysis and evidence-based research to develop well-grounded proposals for building a resilient society in Latvia. PROVIDUS has long-standing expertise in the field of migration policy, providing both data-based assessments and policy recommendations.

The article summarizes recent developments in areas such as the dynamics of temporary and permanent residence permits, employment of third-country nationals, re-migration trends, issues related to integration policy, points highlighted in reports by the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Economics, and good practices in migration and policy development.

It is important to note that, at the time of writing this report, the entry and residence of foreigners in Latvia is governed by the Immigration Law of 2002.[2] In the Ministry of the Interior’s 2018 conceptual report on migration policy it was noted that a new Immigration Law needed to be developed, incorporating the solutions proposed in the conceptual report.[3] As of December 2025, the draft “Immigration Law” has not been adopted, even though the draft was submitted to the Parliament back in 2021.[4]

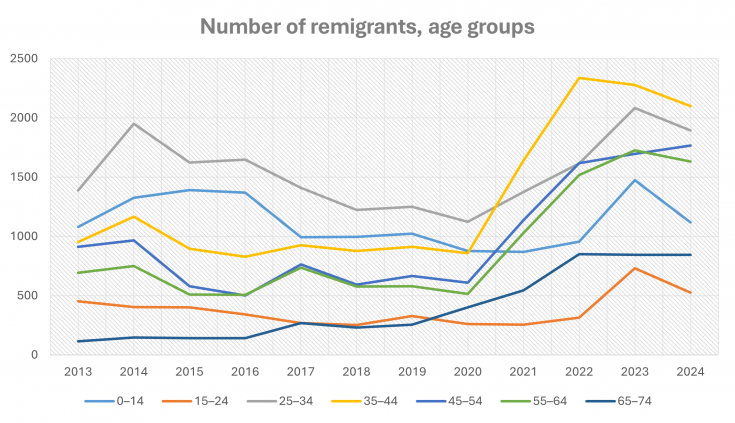

The most significant conclusions of the article relate to the increasing dynamics in the number of temporary residence permits granted, which is mainly associated with the reception of Ukrainian civilians. However, growth is also observed in the number of permits granted in categories “employed worker”, “student” (this category also includes “final-year master’s/PhD student”). Over the past 10 years, the number of remigrants has increased, with a pronounced rise in the 35-44 age group. Most remigrants are of working age, but a significant proportion are also of compulsory school age.

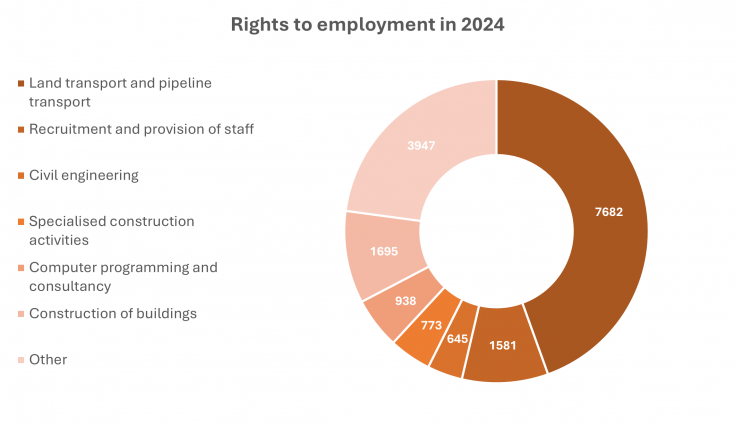

Although the Ministry of Economics notes that Latvia’s labor migration system is aimed at attracting highly qualified workforce,[5] data provided by the Ministry of Interior show that third-country nationals by profession – for example, in 2024 – show that the top five occupations are lower-skilled jobs: truck driver, laborer/assistant, construction worker, tractor-trailer driver, and factory worker.[6] Similar trends have been observed regarding the employment if Ukrainian civilians: in this context, the central challenge in finding work matching qualifications is the lack of Latvian language skills.[7] The lack of language skills is also the main challenge in employment for third-country students in higher education.[8]

In the field of integration policy, the article highlights aspects related to education and employment issues, which give Latvia one of the lowest ratings in the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) assessment – in this context, systematically important long-term integration measures are particularly crucial, aimed at ensuring the successful socio-economic inclusion of migrants in receiving society.

Overall, migration policy can be defined as a set of rules and strategies developed by the state that regulate migration processes, including reception, residence, access to the labor market, family reunification, asylum, integration, and other related processes.[9] In Latvia’s case, it is evident that basic processes and services are defined, but there is a lack of inter-institutional coordination in the fields of migration and integration, as well as a clear long-term strategic vision. For Latvia as a democratic state, it is important to observe its assumed international commitments and human rights principles.

We call on the actors involved in shaping migration policy to define a policy aligned with Latvia’s interests, with a long-term vision of what Latvia’s migration policy should look like in the future, by aligning the visions and diverse interests of actors involved, as well as by speaking more openly about challenges, various possible solutions, and their consequences.

Migration dynamics

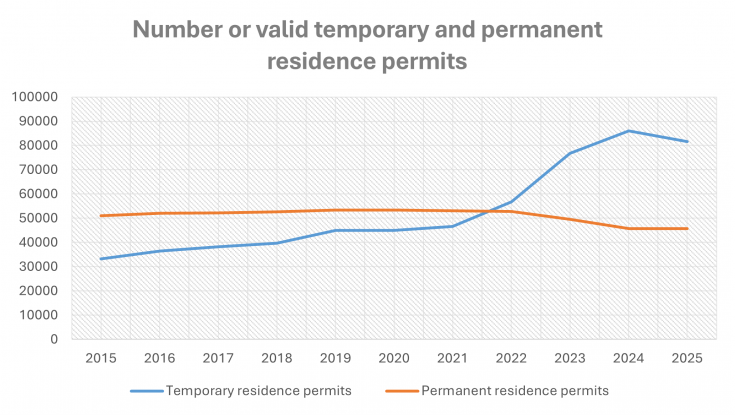

In the context of increasing relevance of immigration-related issues, it is important to examine the data compiled and published by the Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs (OCMA/PMLP). Over the past 10 years, the total number of valid residence permits has increased – particularly since 2022 – while the total number of valid permanent residence permits has decreased (Chart No. 1).

Chart No. 1. Number of valid temporary and permanent residence permits as of December 31 of each year (as of July 1, 2025). Source: OCMA data.

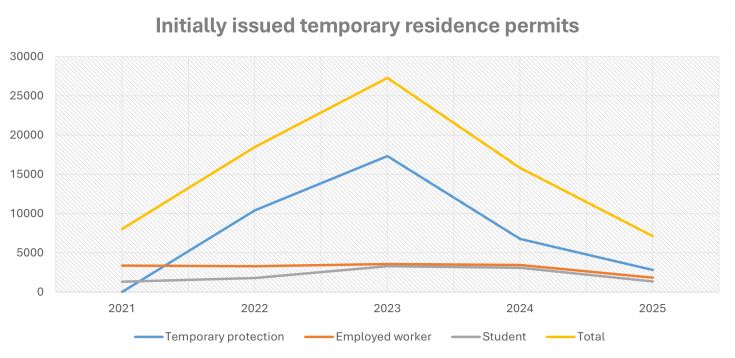

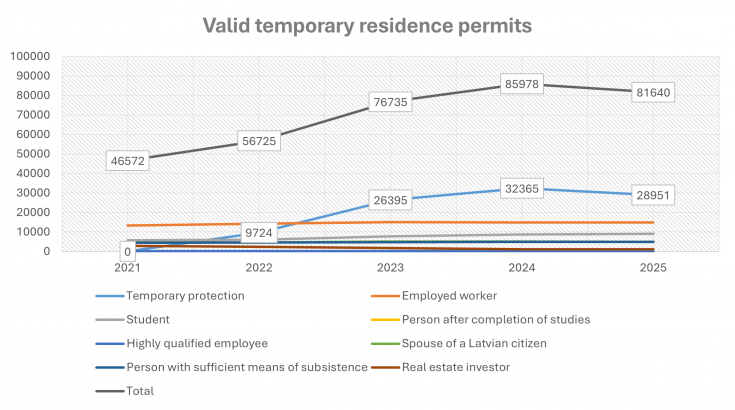

After 2022, most temporary residence permits were initially issued for temporary protection purposes to Ukrainian civilians, with a smaller portion issued to workers and students. The reasons for the dynamics of initially issued temporary residence permits are shown in Chart No. 2. Although the number of students from third countries has been increasing over the past 8 years,[10] the largest number of first-time issued temporary and permanent residence permits (Charts 2 and 3) were issued to Ukrainian civilians following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Chart No. 2. Number of initially issued temporary residence permits 2021-2025 1st half. Source: OCMA

Chart No. 3. Number of valid temporary residence permits (overall) 2021-2025. 1st half. Source: OCMA

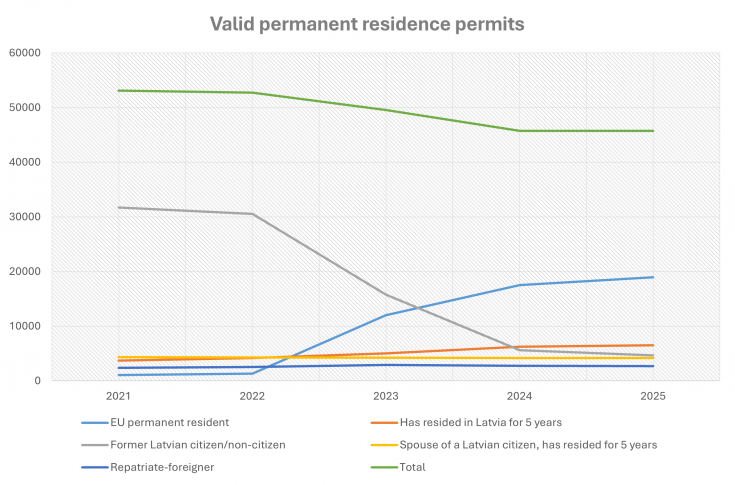

The number of permanent residence permits has remained stable over the past 10 years, with a tendency to decrease (Chart No.1). Looking in more detail of persons with European Union (EU) long-term resident status and of those who have resided in Latvia for 5 years has increased. A decrease is observed in the category of former Latvian citizens/non-citizens (Chart No. 4).

Chart no. 4. Number of valid permanent residence permits (overall) 2021-2025. 1st half. Source: OCMA

Employment of third-country nationals

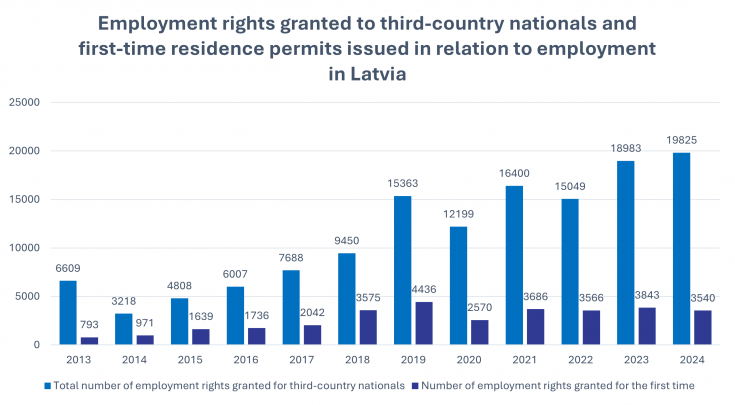

Detailed data on the employment of third-country nationals in Latvia are examined in the annual reports about asylum and migration in Latvia, prepared by the Latvia’s national contact point of the European Migration Network (EMN LV).[11] The data obtained by the EMN LV on the rights to employment granted for third-country nationals show that, since 2013, the total number of temporary residence permits related to employment has increased (Chart No. 5).

Chart No. 5. Number of employment rights granted to third-country nationals and first-time residence permits issued in relation to employment in Latvia. Source: Eiropas migrācijas tīkla Latvijjas kontaktpunkts. Siliņa-Osmane, I., Ieviņa, I. (2025). Par migrācijas un patvēruma situāciju Latvijā 2024. Gadā. Pieejams: https://www.emn.lv/eiropas-migracijas-tikls-publice-patveruma-un-migracijas-parskatu-par-2024-gadu/

In the EMN LV report, the types of employment of third-country nationals in 2024 are summarized, mainly covering the transport sector, staff provision, construction and others (see Chart No. 6).

Chart No. 6. Rights to employment. Source: Eiropas migrācijas tīkla Latvijjas kontaktpunkts. Siliņa-Osmane, I., Ieviņa, I. (2025). Par migrācijas un patvēruma situāciju Latvijā 2024. Gadā. Pieejams: https://www.emn.lv/eiropas-migracijas-tikls-publice-patveruma-un-migracijas-parskatu-par-2024-gadu/

Asylum dynamics

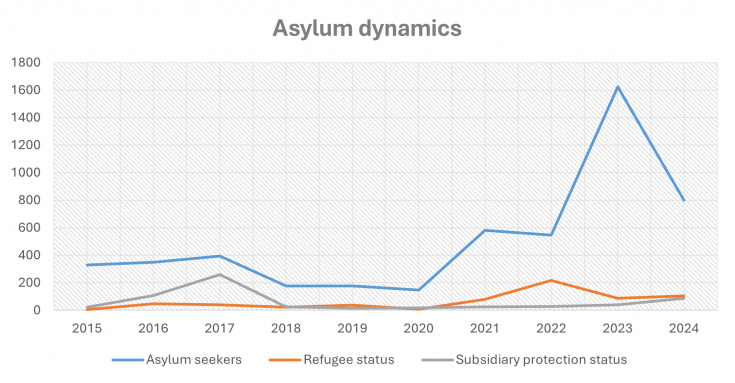

Over the last 9 years, the number of asylum applications has increased, especially in 2023 (see Chart No. 7). Although since 2020 the number of people granted refugee and subsidiary protection status has grown, the data shows that the number of people receiving subsidiary status remains below the 2017 level, and the number of those granted refugee status remains below 2022 levels.

The EMN LV report on the migration and asylum situation in Latvia in 2023 notes that, compared to 2022, the number of asylum applications in 2023 increased threefold. In 2023, most asylum applications were submitted by persons from Syria (348), Afghanistan (307), Iran (206), India (167), and Iraq (65).[12]

Chart No. 7. Asylum dynamics 2015-2024. Source: OCMA (2025). Statistics on asylum seekers. Available: https://www.pmlp.gov.lv/lv/patveruma-mekletaju-statistika

Naturalisation dynamics

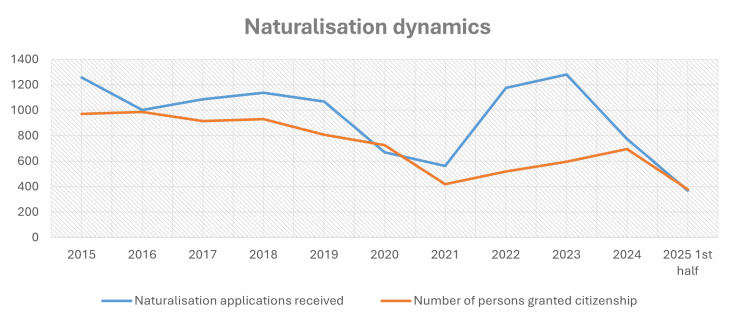

Comparing 2015 and 2024, the number of received applications for naturalisation has decreased, but the dynamics show and increase during two periods – from 2017 to 2018, and from 2022 to 2023. The number of people granted citizenship also shows an overall downward trend, with an observable increase in 2024.

Chart No. 8. Naturalisation dynamics 2015-2025 1st half. Source: OCMA (2025). Naturalisation. Avalilable: https://www.pmlp.gov.lv/lv/naturalizacija

Remigration

Over the past 10 years, the number of remigrants has increased. A pronounced increase is observed in the 35-44 age group. Data shows that most remigrants are of working age, but a significant proportion is also of compulsory school age (see Chart No. 9). According to the conclusions of the Central Bank of Latvia, the experience of remigrants can have a positive impact on the productivity of local companies, but some challenges remain; i.e. remigrants have a lower economic activity compared to the local population.[13]

Chart No.9. Number of remigrants, age groups 2015-2024. Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia (2025). IBR040. Available: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/lv/OSP_PUB/START__POP__IB__IBR/IBR040/

Integration

Immigration is not separate from integration policy. Mechanisms and the set of services that determine Latvian language acquisition, inclusion in the labor market, the education system and other areas are essential for successful integration of newcomers.

The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), which aims to provide an overview of newcomers’ opportunities to participate in society, ranks Latvia in the last place in the EU. In the context of this article, it is important to highlight two areas assessed by MIPEX: education (26 out of 100 points) and labor market mobility (33 out of 100 points).[14]

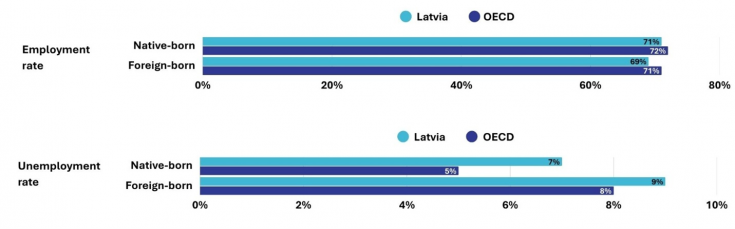

In the context of labor market mobility, one of the challenges is related to the lack of targeted measures for integration into the labor market, while in the field of education there is a lack of systemic long-term support. OECD employment data shows that the employment rate of newcomers in Latvia is slightly below the OECD average (69% in Latvia, compared to an OECD average of 71%). The employment rate of the local population is also slightly below the OECD average. The unemployment rate for both local population and newcomers is above the OECD average (see Chart No. 10). According to OECD data, the employment rate of newcomers is slightly lower, and the unemployment rate is slightly higher, compared to the local population.

Chart No.10. Employment levels of native-born and foreign-born populations in Latvia and OECD. Source: OECD (2025). International Migration Outlook 2025. Available: https://doi.org/10.1787/ae26c893-en

Lack of long-term vision and support in the field of education can lead to challenges in language acquisition, in the learning process, and in participation in tertiary education and labor market in the long term. The challenges in education are more clearly seen in a study carried out by PROVIDUS on Ukrainian civilians in the Latvian education system – the main obstacles are related to insufficient support for learning the Latvian language and the short-term nature of integration measures.[15]

Immigration policy, labor market dynamics

In the context of labor migration, the 2018 policy concept on immigration developed by the Ministry of Interior points to several factors, for example:

- Optimizing the handling of migration-related issues can increase employers’ ability to respond to labor market shortages and can improve opportunities for investment.

- Optimal regulation of labor market immigration will be one of the means of promoting economic growth and competitiveness.

- Labor market forecasts indicate that immigration will be crucial for mitigating the negative effects of declining demographic trends.[16]

It is important to note that, at the time of writing this article, the entry and residence of foreigners in Latvia is regulated by the Immigration law adopted in 2002.[17] The 2018 immigration policy concept states that a new Immigration Law needs to be drafted, incorporating the solutions set out in the concept paper.[18] As of December 2025, the draft law “Immigration Law” has not been adopted, even though it was submitted to the Saeima for consideration back in 2021.[19]

In the informative report “On improving the legal regulation of the residence of third-country nationals” prepared in 2025, by the Ministry of the Interior, several factors related to immigration dynamics are highlighted:

- It is noted that in recent years the number of third-country nationals arriving for employment and study purposes has increased, in view of the Ministry of the Interior there is a growing risk of breaches of residence and employment conditions.

- In the breakdown by occupation, in 2024 and the first half of 2025 third-country nationals were employed mainly in low-skilled occupations, such as truck driver, laborer/assistant, construction worker, tractor-trailer driver, and factory worker. In the medium term, one of the development directions of the human capital plan envisages attracting skilled labor by involving foreign students in the labor market.

- Planned measures include strengthening capacity in the internal affairs sector, expanding control measures, and ensuring the operation of the Society Integration Foundation’s (SIF) one-stop agency to support integration into Latvian society.[20]

In the 2024 informative report of the Ministry of Economics on medium- and long-term labor market forecasts, it is stated that in the long term the population of Latvia will decrease, which will affect the labor market. The migration target scenario indicated by the Ministry of Economics foresees that by 2040 Latvia’s labor market will approach the level of the most developed EU countries, especially in terms of wages, and will increasingly provide a basis for labor immigration. The report notes that “Immigration will play a significant role in ensuring the development of a balanced labor market. In the short and long term, it is essential to ensure the rapid integration of Ukrainian civilians into the Latvian labor market (…) At the same time, as the number of third-country nationals employed in Latvia increases, it is important to reduce risks in the labor market for this target group.”[21]

In the Ministry of Economics report on labor market forecasts, it is additionally indicated that in the medium- and long-term demand will grow mainly for highly qualified professionals – in the medium term in commercial services, public services and construction, in the long term in commercial services, trade, manufacturing and construction. At the same time, the sharpest decline in demand will be in low-skilled occupations, affecting all sectors.[22]

Although the Ministry of Economics notes that the labor migration system in Latvia is oriented towards attracting more highly qualified labor,[23] data from the Ministry of the Interior on the distribution of third-country nationals by occupation, for example in 2024 and the first half of 2025, show that the top five occupations in which third-country nationals are employed are lower-skilled: truck driver, laborer/assistant, construction worker, tractor-trailer driver, and factory worker.[24] Similar patterns were observed in relation to the employment of Ukrainian civilians. In a study carried out by PROVIDUS in 2024, 38.7% of Ukrainians were employed in lower- skilled occupations, 16.1% craftsmen, 14.8% as service and sales workers, 12.7% as skilled professionals, and 0.9% as senior managers. In this context, the central challenge for working a job matching one’s qualifications is the lack of Latvian language skills.[25] A lack of language skills is also a central challenge for foreign students in employment.[26]

What factors shape migration policy?

Migration policy can be defined as a set of rules and strategies developed by a state that governs the migration process, including admission, residence, access to the labor market, family reunification, asylum, integration and other related processes.[27]

Good practices in migration policy include:

- A clear legal framework based on international law (e.g., immigration law, related regulations).

- Clear, data-based objectives, balancing the views of the parties involved, e.g. in the areas of the labor market (skills, labor force), demographic considerations, human rights protection, and cohesion (integration, anti-discrimination).

- Effective coordination between institutions in the areas of home affairs, employment, foreign affairs and social affairs, including cooperation with local authorities, NGOs and other stakeholders.

- Integration policies that promote socio-economic well-being (language learning, education, access to the labor market).

- Safe and clear migration cycle mechanisms: transparent, legally based channels for receiving newcomers, return procedures where necessary, cooperation with the diaspora.[28]

In Latvia’s case, basic processes and services have been defined, but there is a lack of inter-institutional coordination in the fields of migration and integration, as well as of a clear long-term strategic vision. This is clearly reflected in labor market forecasts, which highlight a long-term need for skilled labor that does not correspond to the employment of newcomers in low-skilled occupations. Such a situation indicates a lack of long-term vision regarding what Latvia’s immigration policy should look like in the future, while reconciling the perspectives of the stakeholders involved. For Latvia as a democratic state, it is important to respect its international commitments and human rights principles.

Integration policy cannot be viewed outside the context of migration policy. Latvia’s results in MIPEX point to long-term integration challenges, especially as the number of newcomers increases. It is essential to implement a long-term approach that clearly defines the roles of actors involved in integration (national-level institutions, policy implementers, municipalities and other parties) and aligns the mechanisms for providing integration services to newcomers. It is important to ensure that integration services, such as language learning, labor market integration measures and social inclusion activities, are available without interruption and are not only short-term in nature. The shortcomings are evidenced not only by MIPEX results but also by the experiences of newcomers, for whom insufficient Latvian language skills are a central challenge to employment in jobs matching their qualifications, which can create long-term difficulties for attracting skilled labor and successful integration in general.

PROVIDUS calls for the parties involved in shaping migration policy to define a policy that corresponds to Latvia’s interests, with a long-term vision of what this policy should look like in the future, reconciling the different perspectives and interests of the stakeholders and speaking more openly about the challenges, the various possible solutions and their consequences.

Article in PDF is available here.

Sources:

[1] Saeima (2025). Saeima izveido parlamentāro izmeklēšanas komisiju par problēmām nacionālajā un ES regulējumā saistībā ar masveidīgu trešo valstu pilsoņu ieceļošanu Latvijā. Pieejams: https://www.saeima.lv/lv/aktualitates/saeimas-zinas/35311-saeima-izveido-parlamentaro-izmeklesanas-komisiju-par-problemam-nacionalaja-un-es-regulejuma-saistiba-ar-masveidigu-treso-valstu-pilsonu-iecelosanu-latvija

[2] Saeima (2002). Immigration Law. Available: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/68522

[3] Ministru kabinets (2018). Par konceptuālo ziņojumu “Konceptuāls ziņojums par imigrācijas politiku”. Pieejams: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/297177-par-konceptualo-zinojumu-konceptuals-zinojums-par-imigracijas-politiku

[4] Saeima (2025). Likumprojekts “Imigrācijas likums”. Pieejams: https://titania.saeima.lv/LIVS14/saeimalivs14.nsf/webAll?SearchView&Query=([Title]=*Imigr%C4%81cijas+likums*)&SearchMax=0&SearchOrder=4

[5] Ekonomikas ministrija (2024). Informatīvais ziņojums par darba tirgus vidēja un ilgtermiņa prognozēm. Pieejams: https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/media/20607/download?attachment

[6] Iekšlietu ministrija (2025). Informatīvais ziņojums par trešo valstu pilsoņu uzturēšanās Latvijā tiesiskā regulējuma pilnveidošanu. Pieejams: https://tapportals.mk.gov.lv/legal_acts/707e492f-8bfd-4dc1-801f-3a6b85abd733

[7] Meilija, D., Pelse, D., Kažoka, I., et.al. (2024). Ukrainas bēgļi Latvijā: pieejamie dati, pieredze un sabiedrības attieksme. Pieejams: https://providus.lv/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Providus_research_final_0509-1.pdf

[8] Vārpiņa, Z., Krūmiņa, M. (2025). Starptautisko student integrācija un nodarbinātības iespējas Latvijā. Pieejams: https://arpasaulespieredzi.lv/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Treso_valstu_studentu_nodarbinatiba_2025.pdf

[9] International Organization for Migration (2018). Key Migration Terms. Pieejams: https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

[10] Vārpiņa, Z., Krūmiņa, M. (2025). Starptautisko studentu integrācija un nodarbinātības iespējas Latvijā. Pieejams: https://arpasaulespieredzi.lv/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Treso_valstu_studentu_nodarbinatiba_2025.pdf

[11] Eiropas migrācijas tīkla Latvijjas kontaktpunkts. Siliņa-Osmane, I., Ieviņa, I. (2025). Par migrācijas un patvēruma situāciju Latvijā 2024. Gadā. Pieejams: https://www.emn.lv/eiropas-migracijas-tikls-publice-patveruma-un-migracijas-parskatu-par-2024-gadu/

[12] Eiropas migrācijas tīkla Latvijas kontaktpunkts. Siliņa-Osmane, I., Ieviņa, I. (2024). Ziņojums par migrācijas un patvēruma situāciju Latvijā 2023. gadā. Pieejams: https://www.emn.lv/zinojums-par-migraciju-un-patveruma-situaciju-latvija-2023-gada/

[13] Migunovs, A. (2025). Ko lielāks remigrantu skaits sola Latvijas darba tirgum? Pieejams: https://www.makroekonomika.lv/raksti/ko-lielaks-remigrantu-skaits-sola-latvijas-darba-tirgum

[14] Migration Policy Group (2025). Migrant Integration Policy Index. Latvia. Available: https://www.mipex.eu/latvia

[15] Pelse, D., Stafecka, L., Liepiņa, S. et. Al. (2025). Ukrainas civiliedzīvotāji Latvijas izglītības sistēmā: prakse un izaicnājumi. Pieejams: https://providus.lv/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Ukrainas-civiliedzivotaji-Latvijas-izglitibas-sistema-prakse-un-izaicinajumi.pdf

[16] Ministru kabinets (2018). Par konceptuālo ziņojumu “Konceptuāls ziņojums par imigrācijas politiku”. Pieejams: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/297177-par-konceptualo-zinojumu-konceptuals-zinojums-par-imigracijas-politiku

[17] Saeima (2002). Immigration Law. Available: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/68522-imigracijas-likums

[18] Ministru kabinets (2018). Par konceptuālo ziņojumu “Konceptuāls ziņojums par imigrācijas politiku”. Pieejams: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/297177-par-konceptualo-zinojumu-konceptuals-zinojums-par-imigracijas-politiku

[19] Saeima (2025). Likumprojekts “Imigrācijas likums”. Pieejams: https://titania.saeima.lv/LIVS14/saeimalivs14.nsf/webAll?SearchView&Query=([Title]=*Imigr%C4%81cijas+likums*)&SearchMax=0&SearchOrder=4

[20] Iekšlietu ministrija (2025). Informatīvais ziņojums par trešo valstu pilsoņu uzturēšanās Latvijā tiesiskā regulējuma pilnveidošanu. Pieejams: https://tapportals.mk.gov.lv/legal_acts/707e492f-8bfd-4dc1-801f-3a6b85abd733

[21] Ekonomikas ministrija (2024). Informatīvais ziņojums par darba tirgus vidēja un ilgtermiņa prognozēm. Pieejams: https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/media/20607/download?attachment

[22] Ekonomikas ministrija (2024). Informatīvais ziņojums par darba tirgus vidēja un ilgtermiņa prognozēm. Pieejams: https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/media/20607/download?attachment

[23] Ibidem

[24] Iekšlietu ministrija (2025). Informatīvais ziņojums par trešo valstu pilsoņu uzturēšanās Latvijā tiesiskā regulējuma pilnveidošanu. Pieejams: https://tapportals.mk.gov.lv/legal_acts/707e492f-8bfd-4dc1-801f-3a6b85abd733

[25] Meilija, D., Pelse, D., Kažoka, I., et.al. (2024). Ukrainas bēgļi Latvijā: pieejamie dati, pieredze un sabiedrības attieksme. Pieejams: https://providus.lv/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Providus_research_final_0509-1.pdf

[26] Vārpiņa, Z., Krūmiņa, M. (2025). Starptautisko student integrācija un nodarbinātības iespējas Latvijā. Pieejams: https://arpasaulespieredzi.lv/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Treso_valstu_studentu_nodarbinatiba_2025.pdf

[27] International Organization for Migration (2018). Key Migration Terms. Available: https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

[28] International Organization for Migration (2015). Migration Governance Framework. Available: https://mena.iom.int/resources/migration-governance-framework-migof